Double Star (1956)

The third Annual Science Fiction Achievement Awards were awarded in 1956 at NyCon II, the second World Con to be hosted in New York. By now the awards were beginning to gain respect amongst genre fans, and the list of categories was beginning to slowly resemble the list familiar to modern Hugo voters.

One thing that changed at NyCon II was the introduction of a shortlist of nominees for each award (except, for some reason, the Best Prozine category). These shortlists were drawn up taking recommendations from anyone who fancied nominating a work. These nominations were then screened by a committee of recognised experts in the field to decide if the works qualified for inclusion. Members and attendees of NyCon II received a ballot and were asked to vote for the one nomination in each category they felt most deserved the award.

For the Best Novel category in 1956, the five works that made it on to the shortlist were Robert A. Heinlein’s Double Star, Leigh Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow, Asimov’s The End of Eternity, C. M. Kornbluth’s Not This August and Three to Conquer by Eric Frank Russell. While it’s fair to say in hindsight that at least three of these works are still considered classics of the genre, once the votes had been cast and counted one title stood out as the clear and decisive winner: Heinlein’s Double Star.

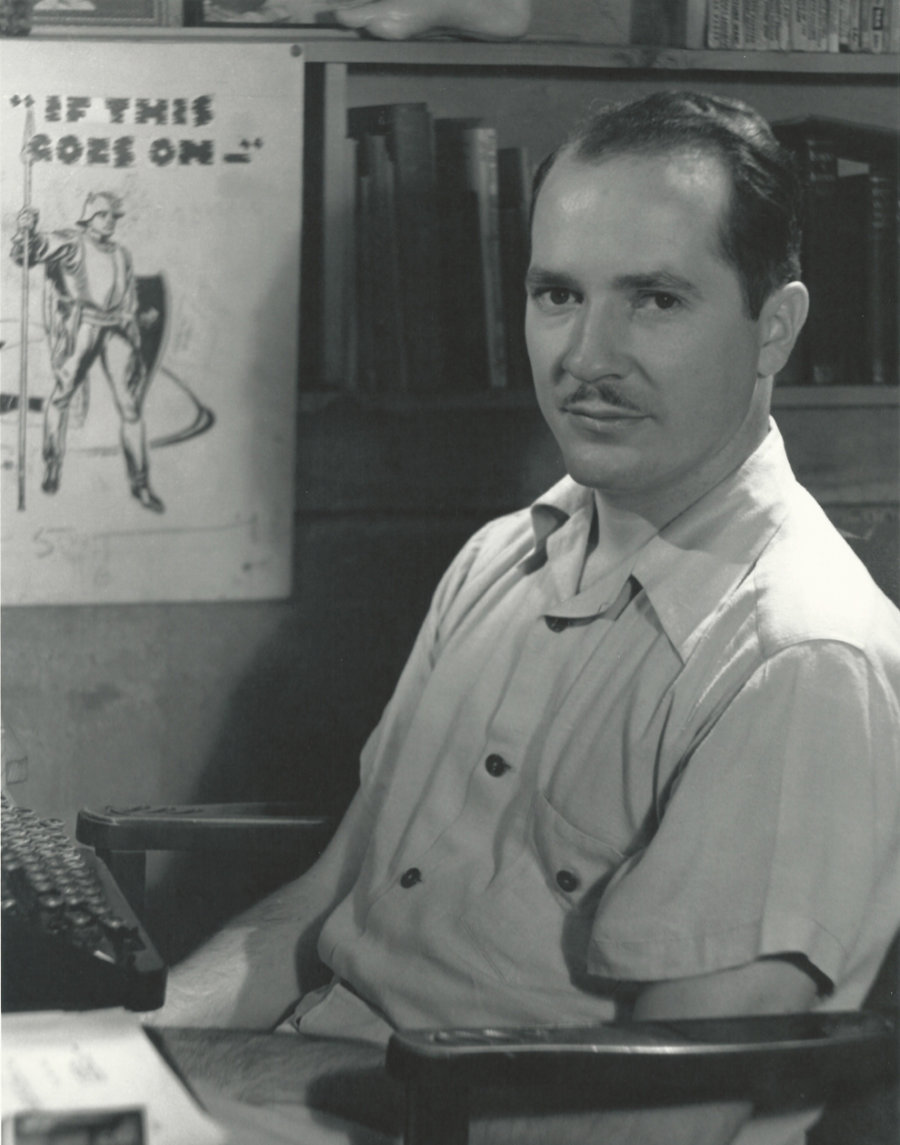

The Author: Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988)

Robert Anson Heinlein was already a well-established science fiction writer by the time he won his first Hugo Award in 1956. He’d already had an even dozen novels published prior to Double Star, most of which were published by Scribner’s as part of what is now known as Heinlein’s “juvenile” series. He also had a sizeable back catalogue of short stories to his name, appearing in several of the main genre-related magazines of the time.

In his earlier years Heinlein served as a radio operator and gunnery officer in the Navy, reaching the rank of lieutenant before leaving the service in 1934 following a bout of tuberculosis. He tried to re-enlist when World War II broke out but was denied and instead supported the American war effort by working as a civilian engineer at the Naval Air Experiment Centre in Philadelphia, alongside fellow authors Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague de Camp.

His first published story, “Life-Line”, was originally written as an entry for a contest but eventually got printed in the August 1939 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, earning him far more than the contest’s first prize payout. This was followed by several more short stories, and in 1947 he became one of the first sci-fi writers to break out of the pulp market with the publication of The Green Hills of Earth in the Saturday Evening Post.

While many of his later works introduced a number of controversial (and in some cases questionable) themes and ideas, his earlier works were more typical of the era, consisting mainly of stirring adventures, often with young, capable protagonists. While he was aware of the editorial limitations and restrictions placed on him by his publishers, he always somehow managed to introduce mature, adult themes into his works, especially those aimed at his juvenile audience.

In addition to winning four Hugos for Best Novel in his lifetime, Heinlein was also the first author to be named as Grand Master by the Science Fiction Writers of America in 1974/75. In 1998 he was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame, and has a main belt asteroid (6312 Robheinlein) and a crater on Mars named after him.

Along with Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov, Heinlein is named as one of the “Big Three” writers, and has often been identified as the “dean of science fiction”. He is, without a shadow of a doubt, one of the most influential sci-fi writers of the twentieth century and even today is still considered by many to be one of the greatest genre writers of all time.

The Book: Double Star (1956)

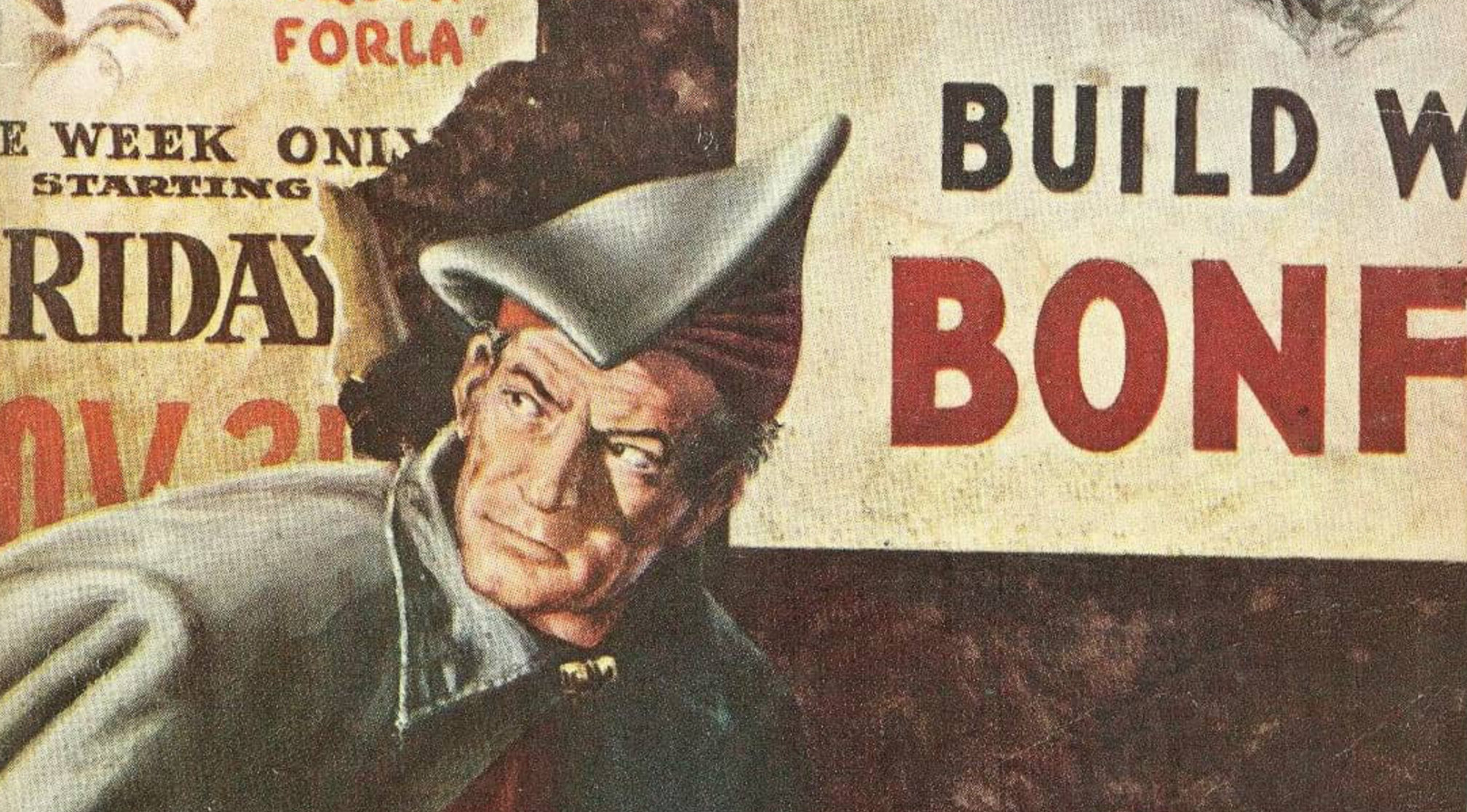

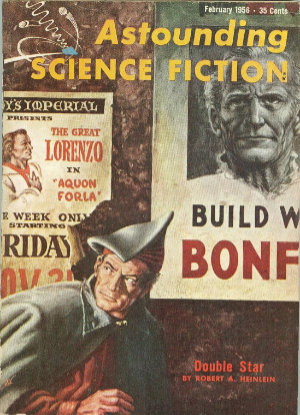

Double Star was first serialised in the pages of Astounding Science Fiction, appearing in three instalments in the February, March and April 1956 issues (July, August and September in the UK). In the same year it also appeared in hardback, published by Doubleday in the US.

It tells, in first person, the tale of Lawrence Smith, aka The Great Lorenzo, a down-and-out actor on his last coin when he is approached by a spaceman in a bar and offered a job impersonating a known public figure. Quickly finding himself drawn into an interplanetary conflict, it’s only once he’s on his way to Mars that he learns the man he’s going to impersonate is none other than John Joseph Bonforte, one of the most prominent politicians in the solar system. Bonforte has been kidnapped by his political rivals, and it falls to Smith to take Bonforte’s place in an important Martian ceremony.

Despite his opposition to Bonforte’s political views, Smith begrudgingly agrees to take on the role. As he studies recordings of Bonforte’s appearances and learns more about the man he is impersonating he gradually grows to like him, perhaps even admire him. When Bonforte is finally rescued and it’s revealed that he is medically incapable of returning to public service, Smith is convinced to continue in the role, taking on the mantle of Supreme Minister in Bonforte’s place.

Setting aside his own anti-Martian prejudice, Smith is called upon to assume Bonforte’s views and fight for voting rights for the Martian people. When the governing party unexpectedly announces its intention to step aside Smith is forced to stand in an election, a task that requires that he call upon every ounce of his craft.

The Review

It’s hardly surprising this book won the Hugo for Best Novel in 1956. It is arguably one of Heinlein’s finest works, and certainly one of his best first-person narratives. The character of Lawrence Smith is fully realised, with a strong sense of identity and Independence that eludes many of Heinlein’s other first-person characters. What’s more, that sense of identity slowly morphs throughout the story as Smith begins to take on the persona of Bonforte. This gives Heinlein a chance to question what makes a man, what identity is in the first place, and he does a masterful job of presenting his findings here.

The trope of a double taking on the identity of a person of importance is an old one, and includes works by Mark Twain (The Prince and the Pauper) and Anthony Hope (The Prisoner of Zenda) being two examples. Even so, Heinlein manages to take something familiar and give it a new spin, a surprising freshness. While the outcome is almost predictable, it’s the way he tells the story that keeps us reading. This is Heinlein showing us just how good he can be when he wants to be.

Conclusion

While there are a few elements in this book that are truly dated to a modern reader, most notably the Martian race, the core themes of Double Star are still relevant today. This is a story that resonates regardless of where or when you read it, and it’s almost a certainty that if it were released today it would be in with a good chance of making the Hugos shortlist. It’s not hard to understand why this book has stayed in print since its original release; in 2012 it was included in the Library of America’s two-volume set American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s, and in 2013 it was added to Gollancz’ SF Masterworks series.

Heinlein went on to win three more Best Novel Hugos during his lifetime, along with more than a few Retro Hugos in more recent years. Even so, in my opinion this is still one of his best books and easily deserves four-and-a-half out of five stars. It truly is one of the classics of 50’s science fiction, and an excellent place to start if you’ve not previously read any of Heinlein’s work.

Coming Next

For some reason, the committee behind LonCon in 1957 decided to only include non-fiction categories in their Hugo Awards, so there was no Best Novel that year. However, by the time the baton had been passed to Solacon in 1958 the fiction categories were once again included. Next month we’ll take a look at that year’s winner, an unusual tale of an epic war spanning all of human history. So tune in next month when we’ll be cracking the spine on Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time.