The Demolished Man (1953)

In 1953, the attendees and members of the eleventh World Science Fiction Convention (aka The 11th WorldCon, or Philcon II) were asked to do something they’d never done before: to vote for the writers, editors, artists and fans they felt had distinguished themselves in the past year with awards to be given at the First Annual Science Fiction Achievement Awards. And thus was born the spectacle we now know as the Hugo Awards.

In that first year there were no shortlists of nominations; whoever got the most votes in the first (and only) ballot won the award, and while the organising committee of Philcon II clearly hoped this would become a respected tradition, there was no guarantee at the time there would be a Second Annual Science Fiction Achievement Awards. Even so, the fans got behind their favourite writers and artists of the year and all in all seven categories were voted upon and nine shiny retro rocket ships were given out (two categories ended in a tie, being Best Professional Magazine and Best Cover Artist).

Looking back at the novels that got released in the twelve months or so running up to The 11th WorldCon there are some familiar titles that may well have made it onto a ballot, had one existed: Asimov’s Foundation and Empire, Heinlein’s The Rolling Stones, Vonnegut’s Player Piano, and Clarke’s Islands in the Sky all stand out as being potential nominees, just to name a few. However, given the lack of a shortlist, and apparently a lack of any sort of voting record it’s hard to know who might have won the first ever award for Best Novel, but we do know who did win: Alfred Bester, for The Demolished Man.

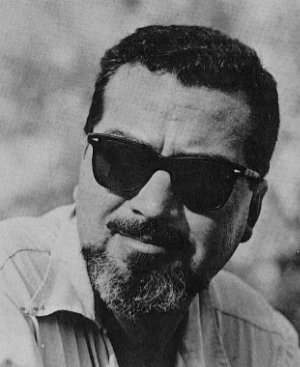

The Author: Alfred Bester (1913-1987)

Alfred Bester was an American science fiction author, amongst other talents, and got his break by winning an amateur story contest in Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1939, for which he was awarded the then princely sum of $50, roughly $900 in adjusted money these days. This first success set the ball rolling, but it wasn’t until 1952 that his first novel, The Demolished Man, appeared as a three-parter in Galaxy Science Fiction.

After winning the inaugural Hugo Award for Best Novel with that first masterpiece, Bester went on to write and publish four more science fiction novels, including the much-respected classic The Stars My Destination (1956). First published as a book in the UK as Tiger! Tiger! this was later serialised, again by Galaxy, and has since been described by some as a spiritual ancestor to cyberpunk.

Amongst his other genre works are The Computer Connection (1975), Golem100 (1980), and The Deceivers (1981). There’s also a posthumous novel, Psychoshop (1998) which was started by Bester and finished by Roger Zelazny.

So influential was he as an author that J. Michael Straczynski paid homage to him by naming a recurring Babylon 5 character after him, making him a senior member of the show’s PsiCorp organisation, which may in turn have been influenced by the Espers League in The Demolished Man.

Shortly before his death in 1987 the Science Fiction Writers of America named Bester the ninth SFWA Grand Master, and in 2001 he was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. Though The Demolished Man was his only work to win an award he made a lasting impression on the sci-fi landscape, with fellow author Harry Harrison describing him as “…one of the handful of writers who invented modern science fiction.”

The Book: The Demolished Man (1952)

The Demolished Man is a police procedural with a sci-fi twist. It concerns itself with the actions of Ben Reich, the novel’s antagonist, who sets out to commit the perfect murder in a world where telepaths, called Espers or ‘peepers’ in the narrative, can read everyone’s thoughts as easily as most people breathe.

Reich, the paranoid owner of the commercial cartel Monarch Utilities & Resources, is convinced that his rival, Craye D’Courtney of the D’Courtney Cartel, intends to buy out Monarch and rob him of his heritage. Desperate to avoid this outcome, Reich offers D’Courtney a merger, but when his fractured psyche misinterprets D’Courtney’s acceptance as refusal instead, Reich sets about enacting his fiendish plan. The only problem is, if Reich is caught committing murder he faces Demolition, a terrifying punishment that’s not described until the end of the book.

Hiring a talented and powerful Class 1 Esper to hide his murderous impulses from other peepers, Reich devises the perfect murder, drawing several unwitting accessories into his plan as he works towards D’Courtney’s death.

The first part of the novel follows Reich as he pulls together the trappings required to commit his crime, and culminates in D’Courtney’s death. However, despite his meticulous planning the murder is witnessed by D’Courtney’s daughter, who manages to evade Reich and escape into the night with the murder weapon.

The rest of the novel focuses on Police Prefect Lincoln Powell, another Class 1 Esper assigned to investigate the murder. It doesn’t take Powell long to identify Reich as the culprit, but without irrefutable evidence there’s little he can do to bring the man to justice. What follows is a game of cat and mouse that takes in most of the solar system as the two men try to outwit each other, while also simultaneously trying to find D’Courtney’s missing daughter.

The Review

It’s easy to see why this book garnered so much positive feedback when it first got published. It uses familiar tropes from detective fiction, a popular genre at the time, and transposes them into a forward thinking future where crime is almost non-existent and decadence seems to be the order of the day. The wealthy, pampered citizens of Bester’s 24th Century are happy with their lot in life, even those who have to work, and while there is the seedy underclass that’s so integral to any detective story, even this seems mostly to be a choice, rather than a result of circumstance.

In terms of the prose, Bester’s style is punchy and immediate. For the most part what you see is what you get, which leaves the reader free to fully appreciate the in-depth character study of both Reich and Powell. It also cunningly obfuscates the implication of a society being slowly and subtly reshaped by the telepaths. We’re so blinded by the rapid-fire manoeuvring, misdirection and manipulation going on between the two principal characters that we barely register what’s going on behind the scenes.

In some respects this is very much a novel of its time. The decidedly fifties slang used in dialogue, the concept of Espers and telepathy as an accepted part of the setting, the colonisation of large parts of the solar system without need for sealed habitats, and so on make this very much a product of the post-war, pre-space age era. It’s an optimistic view of a future that never happened, and never will, and yet it’s a charming view despite the obvious inaccuracies. Even allowing for the pseudo-totalitarian presence of the peepers listening in on your every thought, it’s still a future you might want to visit.

Even if you take into account the dated elements, this is still an exemplary novel. It draws you in and keeps you reading, never really sure where the plot is going to take you next. In this respect it perfectly encapsulates the detective novels it aims to emulate, keeping you on your toes with twist after twist. Even though you know whodunnit, you keep reading because you want to know how the bad guy’s going to get his comeuppance at the end of the story. And when that ending comes, it’s nothing like you expected.

Conclusion

All in all this is a fantastic book and it’s hardly surprising it won that first Best Novel award back in 1953. When you compare it to the other works that came out at the same time it easily holds its own against the established talent of the likes of Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke. For a debut novel it truly stands out, and held the promise of greater things yet to come.

What’s more, if you take out the obvious fifties dialogue and replace it with something more up to date it wouldn’t be out of place alongside some of the works making their way on to the Hugo ballots of the modern age. It still stands the test of time, and was one of the original titles included in Gollancz/Millenium’s SF Masterworks series at the turn of the century. As Harry Harrison said in his introduction to the 1996 reprint, it’s “… a first novel that was, and still is, one of the classics.”

Coming Next

Next up I take a look at the 1955 winner, a story of a machine that has the power to optimise the brain and gift you with eternal youth, as long as you’re willing to abandon your prejudice at the door. So join me next month when I’ll be reading They’d Rather Be Right (aka The Forever Machine), the book that’s often been described as the worst ever winner of the Hugo Award.