Rocketship Galileo by Robert A. Heinlein

**This review may contain spoilers**

Rocketship Galileo is the first book that Heinlein had published, and as one of his works aimed at younger (juvenile) readers is heavy on action and adventure but light on heavy thinking. It’s also one of the earliest Heinlein books I remember reading as a pre-teen and still holds a strong appeal for me despite the passage of time.

It’s quite easy to look at this book and criticise the content, the tone and mood of the story, or the science, but what you have to bear in mind is that this book was first published in 1947, almost seventy years ago and a full decade before Russia managed to successfully put the first man-made object into orbit. Despite this, Heinlein managed to get a lot of the science right, and even managed to include some didactic science and technology for the more inquisitive reader to absorb.

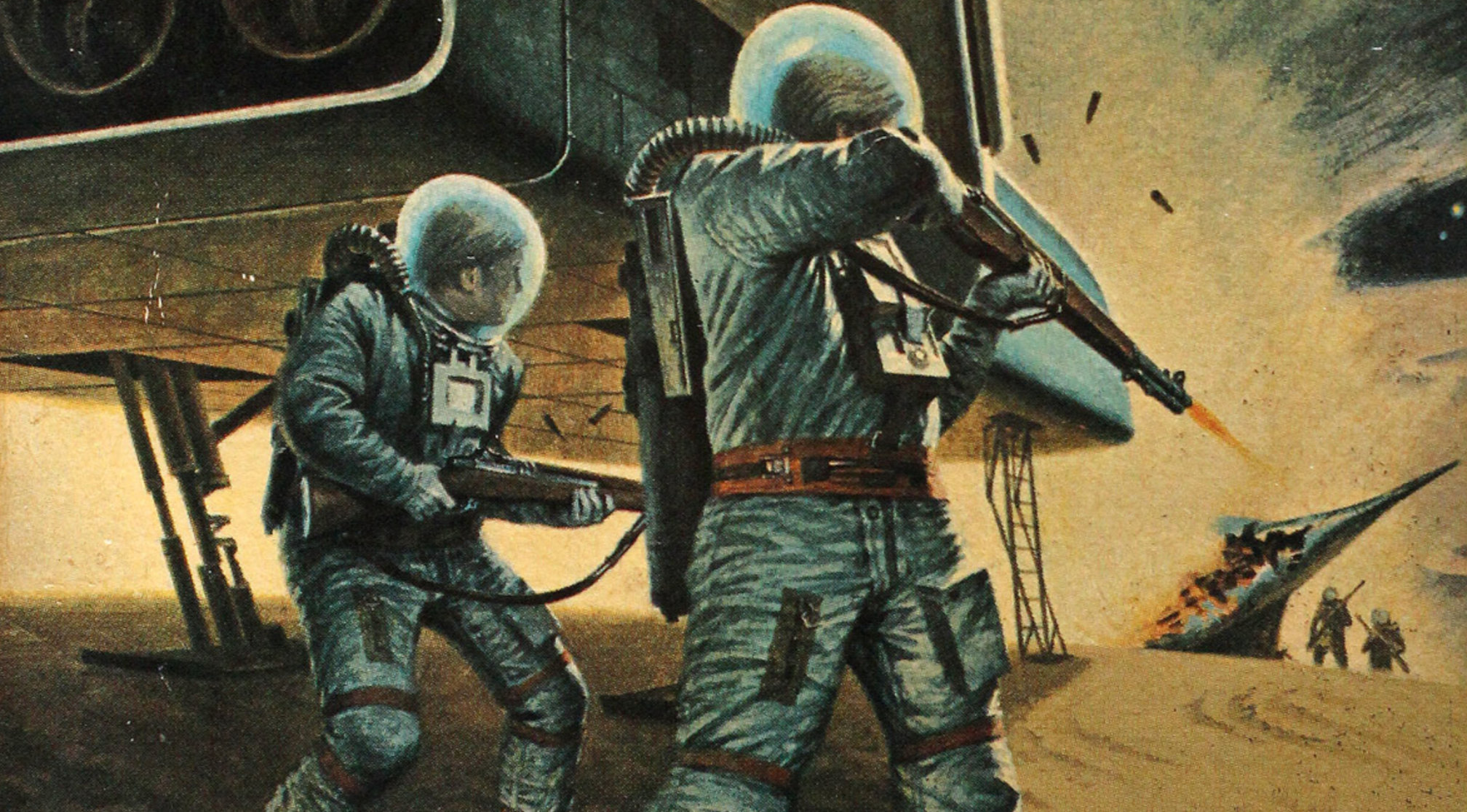

The story itself may seem trite and overly optimistic to the modern reader; a trio of teenage boys, with the help of a slightly eccentric uncle, equip their own atomic rocket ship and make what they think is the first successful trip to the moon. There they find evidence of an extinct lunar civilisation as well as a secret base full of Nazis intent on destroying all the cities of the world. Suffice to say the boys thwart the plans of the Nazis and return to earth safe and sound by the end of the book.

To modern sensibilities it’s easy to see how that plotline can seem a little naive and simplistic, but this is one of the earlier examples of sci-fi space adventure, written only a few short years after the end of the Second World War during a period when hope for the future and fear of the past mixed in equal portions.

What this book does show is Heinlein’s hope (or perhaps belief) that the younger generation of his time held the potential to lead America, and perhaps the world, into a brighter, more enlightened future. It shows an optimistic view of the post-war years, in which the quest to reach beyond this planet would play an important role. It would be twenty-two years more before the human race finally set foot on the moon but even in the mid-forties Heinlein was envisaging such a thing happening and telling us, “this is the next big adventure.”

I would recommend this book (along with a great many more by Heinlein, as well as Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, and all the other great writers of the Golden Age of Sci-Fi) to any fan who wants to see where modern science fiction has come from. I would also recommend it to anyone who thinks that modern sci-fi is perhaps a little too dark and dystopian and who wants something a little more optimistic and fun.