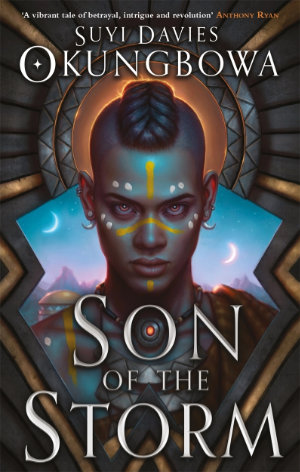

Son of the Storm by Suyi Davies Okungbowa

In the ancient city of Bassa, an outsider with pale skin arrives with a magic that most believe to be no more than a myth. For the young scholar Danso, the outsider represents a way to escape the limitations of the life planned out for him, while for Danso’s intended, Esheme, and her mother Nem, the magic that the outsider brings represents a path to a power greater than she ever imagined possible. But there is more at stake than any of them realise, and before long the very fabric of Bassai society begins to unravel.

This is not your typical western fantasy novel, based as it is in a West-Africa inspired setting. While there are elements of the Bassai culture and society that might seem familiar to most readers, the core of the book, and the way in which the different castes and groups interact with each other, and the stratification of the society as a whole, makes for an intensely different experience to the traditional fantasy tale most of us have grown up with. And honestly, this alone makes Son of the Storm one of the best new fantasy books I’ve read in a long time.

The setting is remarkably well established, bringing in elements of ecological collapse, colonialism, and colourism that might not necessarily make it into a more western-based work. It also has one of the most intriguing magic systems I’ve come across in a long time, with very clearly defined consequences for the magic users, as well as set rules on who can use the magic, and how. That said, the magic itself only plays a minor role in the story, with most of the narrative being centred on the characters, their interactions with each other, and the way their individual journeys are inextricably linked.

Written in a style that carries more than a hint of the author’s Nigerian heritage, the narrative starts off quite slowly, but once the action starts to heat up, the flow of the story increases, and before long you’re being pulled along at a crazy pace. You feel Danso’s awe and wonder as he begins to learn the truth of outsider Lilong’s origins and abilities, but you also feel Lilong’s fear of the potential for upheaval Danso and the rest of the Bassani represent. With Esheme and Nem, you are drawn along by their need to master the power that has dropped in their hands, though you are never left in any doubt that should they succeed, the outcome will be bad for everyone else. Even the ostensibly secondary characters, such as Zaq and Biemwensé are given their full measure of development along the way, and voices of their own which stand out in the narrative. If this is any indication of the sort of writing we can expect from Okungbowa going forward then I am genuinely excited to see more.

If you want to read something new and different, then this is one I’d strongly recommend. I’m not quite ready to give it a full five stars just yet, but it’s not far off. A decent four-and-a-half stars, and strong desire to read the next part of this truly remarkable story.