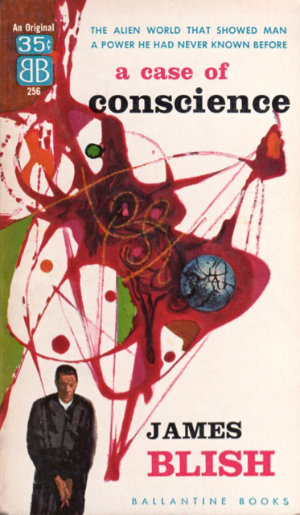

A Case of Conscience (1959)

The 1959 Annual Science Fiction Achievement Awards were awarded at the 17th Worldcon in Detroit, more commonly known as Detention, and once again there were changes made to the overall shape and substance of the Hugos, as they were now affectionately known. In addition to the changes to the list of categories being awarded, perhaps the biggest change was the inclusion of an official nomination round. Unlike in ’57, where nominations were nothing more than suggestions made by those who could be bothered, the process adopted in ’59 included sending out an official nomination ballot through various fandom circles, though as the full rules of the selection process still hadn’t been defined the final ballot had as many as ten nominations (plus No Award) in some categories.

This new approach of letting the fans set a shortlist of nominees led to five titles appearing on the 1959 ballot, consisting of Poul Anderson’s We Have Fed Our Seas (aka The Enemy Stars), Algis Budrys’ Who?, Heinlein’s Have Space Suit – Will Travel, Robert Sheckley’s Time Killer (aka Immortality, Inc.), and of course, the book that walked away with the shiny rocket, James Blish’s A Case of Conscience. Unfortunately, the award committee still hadn’t had the idea to publish the vote counts at this stage, so there’s no record of what order the runners-up placed, so we don’t know how close the votes were.

What does stand out about the shortlist for 1959 is just how different each of the five novels are; the Heinlein is a juvenile space adventure (what would now be called YA), the Anderson is a space opera adventure, the Budrys examines identity in a Cold War SF thriller, Sheckley explores consciousness transfer in a near-future SF, and Blish brought us a religious SF allegory. They couldn’t be more disparate, and yet each one of them is a top class example of sci-fi at the time.

The Author: James Blish (1921-1975)

James Benjamin Blish was an American SFF writer, probably best known for his Cities in Flight series and his work on the Star Trek novelisations he wrote with his wife, J. A. Lawrence. He’s also credited with inventing the term “gas giant” to refer to large planetary bodies, which is just awesome.

His writing career began in 1940, with the publication of his first short story, Emergency Refuelling, in the magazine Super Science Stories, though it wasn’t until his story Chaos, Co-ordinated (co-written with Robert A. W. Lowndes) appeared in the 1946 issue of Astounding Science Fiction that his work got any real circulation. Even so, he didn’t truly pick up any critical acclaim until the publication of his Cities in Flight series in the 1950s. These stories followed a group known as the Okies, humans who journeyed through space on massive city-ships powered by spindizzy antigravity drives.

As well as being a writer, Blish was also one of the first literary critics of science fiction, and judged works within the genre by the same set of standards that were used to judge more “serious” works. Writing for various fanzines throughout the 1950s under the pen name of William Atheling Jr., he would often take to task his fellow authors for everything from grammatical mistakes to errors in scientific understanding, and was just as critical with magazine editors who chose to publish such works.

A Case of Conscience was Blish’s only Hugo Award in his lifetime, though he was nominated for Best Novella twice in 1970, and picked up a couple of Retro-Hugos in 2004 (Best Novella and Best Novelette), as well as a couple of nominations for the Nebula Awards in 1965 and 1968. In 1977 the British Science Fiction Foundation inaugurated the James Blish Award for science fiction criticism, and in 2002 he was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

The Book: A Case of Conscience (1958)

A Case of Conscience started life as a novella, originally published in the September 1953 issue of If magazine, and was extended to novel length in 1958, incorporating the original novella as the first part of the greater whole. The novel also forms the first part of a loose trilogy of works known collectively as the After Such Knowledge trilogy, with the second part being Doctor Mirabilis, and the third part being the two novellas Black Easter and The Day After Judgement.

The novel mainly follows Father Ramon Ruis-Sanchez, a Jesuit priest and biologist assigned to the distant planet of Lithia to determine if it can be opened up to wider human contact. Seemingly a garden paradise, Lithia and its inhabitants cause concerns for the priest, and following an encounter with Chtexa, one of the local inhabitants he has grown close to, he calls for a complete and irrevocable quarantine of the world for all time. To his mind, Lithia is nothing less than a creation of Satan, a place of peace, logic, and understanding absent of the presence of God. Unfortunately, he is opposed by his colleague, the physicist Cleaver, who wants to recommend using Lithia as a factory for producing fusion bombs in massive quantities, forcing the team into a stalemate.

As the humans are preparing to leave Lithia, the Lithian Chtexa presents Father Ruis-Sanchex with a gift, a sealed jar containing Chtexa’s own fertilised egg. The Lithian wants the priest to take his offspring to Earth, to be born and raised amongst humans. Father Ruis-Sanchez is clearly shocked by this, but is unable to refuse before Chtexa leaves and the rocket carrying the survey team home prepares for launch

Back on Earth, the hatchling is born with all the knowledge required for survival, imparted through the Lithian DNA, though thanks to the hatchling’s limited environment during development much of this knowledge is either lost or suppressed. Even so, the young Lithian soon proves to be a hit with the disillusioned portions of human society, and after being declared a citizen of the UN is given his own news show, which he uses to question the efficiency and structure of human society.

As this is going on, Father Ruis-Sanchez is called to Rome to face judgement for his views on Lithia, which many within the church consider to be a heresy of the greatest form. Expecting to be excommunicated for his sins, the priest is summoned to a special interview with the Pope, who points out that rather than being a creation of the Adversary, the world of Lithia and all it contains may be nothing more than an elaborate illusion, a deception which the church is willing to concede might be within Satan’s power. The Pope also points out that Father Ruis-Sanchez could have easily tested this theory by performing an exorcism on the planet itself, though as the priest points out, exorcism has been all but abandoned by the Church. As a final mercy to Father Ruis-Sanchez, the Pope tells him that if he can somehow complete the exorcism and rid the world of this diabolic threat, then the church will welcome him back with full forgiveness.

At the same time, it is revealed that the physicist Cleaver has managed to persuade the UN to accept his proposal in part, and has been sent back to Lithia to begin production and storage of fusion power. However, this work entails tearing down large swathes of the world’s forests, and eventually leads to the destruction of what is ostensibly a sacred site and the heart of the Lithian navigational and telecommunications infrastructure.

Shortly after Ruis-Sanchez’s departure from Rome, Egtverchi makes his final broadcast in which he invites his followers to rise up against the state, telling them to rip up their identity papers and refuse to obey the commands of the ruling powers. Despite his insistence that the mob remain non-violent, a riot does break out, during which one of the survey team is killed, giving Ruis-Sanchez the motivation he needs to follow the Pope’s instruction. When he later gets a chance to observe the world of Lithia in real-time using a newly developed telescope, he learns that Egtverchi has escaped back to his homeworld, and witnesses first hand the devastation Cleaver’s experiments are creating on the once pristine garden world.

As Cleaver prepares to activate his reactors, on the Moon Father Ruis-Sanchez intones an exorcism, and the observers watch as Lithia explodes. Whether this is down to Cleaver’s experiments, or Ruis-Sanchez’s prayer is left deliberately ambiguous.

The Review

There’s a lot to take in with this book. It’s definitely one of the more unusual science fiction works of the era, and while on the surface it does seem to be primarily a religious tale, it is essentially a story about one man’s crisis of faith. In effect, Father Ruis-Sanchez’ journey in the book is the case of conscience the title alludes to.

The story as whole raises some big questions about the nature of faith, not just from a religious standpoint but also from a moralistic or idealogical point of view. It also touches on the question of what it is to be a human, using the character of Egtverchi to highlight the failures of the human society presented in the book.

The writing is surprisingly readable, though sometimes it can get a bit bogged down in exposition and explanation, especially in the first half when Father Ruis-Sanchez is trying to explain his reasoning for calling for a quarantine of Lithia. Even so, this is not an easy book to get through. There are a lot of thematic twists and detours taking place throughout the narrative, and even a few seemingly loose threads, the most obvious of which is the ambiguity of the ending itself. It’s very easy to get lost in some of the arguments Blish makes through his characters, and this is not helped by the genuinely alien nature of the native Lithians, or the obstinately contrary nature of Egtverchi.

All in all, I enjoyed this one more on a second reading than I did the first time round, and may have to revisit the rest of the series to see if they too have more to offer.

Conclusion

So, did it deserve to walk away with the shiny rocket in 1959? To be honest, I’m inclined to argue that each one of the books on the ballot that year were potential winners. 1959 seems to have been an exemplary year for good sci-fi, and fans at the time had a wide variety of story types to choose from. It’s not hard to see why Blish got the award, but I’m sure I’d be saying pretty much the same if any of the others listed above had pipped A Case of Conscience to the post. In fact, when it comes to examples of the best of classic sci-fi, the five books on the 1959 Hugo ballot are a great place to start.

Coming Next

In 1960, Worldcon moved to Pittsburgh, along with the seventh Annual Science Fiction Achievement Awards, and a certain man by the name of Robert walked away with his second shiny rocket for his now-classic novel, Starship Troopers.