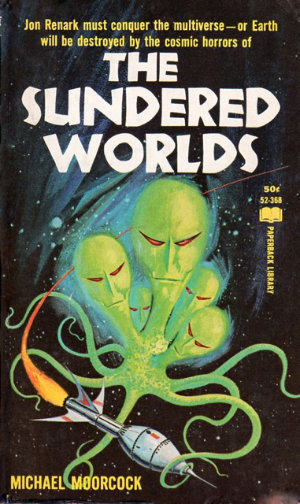

The Sundered Worlds

I’ll be starting my journey through the many worlds of Michael Moorcock’s multiverse with the strange and unusual science fiction novel, The Sundered Worlds. This is one of Michael Moorcock’s earliest novels, published in 1965 alongside a handful of other works including Stormbringer, The Kane of Old of Mars trilogy, and The Fireclown. While it’s far from being one of his better known works, it is the first novel to fully explore the idea of the multiverse that would come to dominate much of his later works, the Eternal Champion cycle in particular.

As one of Moorcock’s first novels, it introduces a number of themes that would later become familiar to regular readers, including the idea of the Eternal Champion itself, and the ever-present effect of chaos and entropy. It also includes the seeds for what would eventually become Moorcock’s grand cosmology, and in some respects could even be seen as the origin of everything that comes after.

So let’s take a look at what The Sundered Worlds have to offer a traveller of the multiverse.

A Brief Publication History

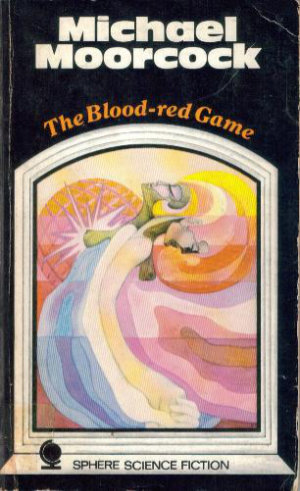

The novel started life as a fix-up of two earlier novellas, the first also called The Sundered Worlds (Science Fiction Adventures #29, 1962), the second being The Blood Red Game (Science Fiction Adventures #32, 1963), and over the years since its initial publication has gone through a few minor changes. In 1970 it was republished in the UK as The Blood Red Game (natch), a title it held on to until 1992 when Roc republished it under its original name. One change made to the Roc edition was to present the narrative in two halves, matching the breakdown of the original novellas, though to avoid too much confusion the first half was renamed as The Fractured Universe.

The most recent incarnations of the novel have appeared in a couple of omnibus editions, specifically the White Wolf omnibus, The Eternal Champion (1994) and the Gollancz omnibus Moorcock’s Multiverse (2014). This last one is said to be the author’s most definitive edition of the novel, and as such is the one I’ll be drawing from for the purpose of this article.

What’s it About?

The basic premise of the novel is that the universe is shrinking, so protagonist Renark the Wanderer and his loyal sidekick Asquiol of Pompeii go looking for a way to save the rest of the human race from inevitable doom. Along the way they travel to an improbable star system that appears and disappears periodically like some sort of cosmic Brigadoon, and meet with a race of beings who claim to have created everything in the multiverse. These beings, the Originators, gift Renark and Asquiol with the knowledge they need to save humanity, as well as granting them the ability to perceive the multiverse in all its glory. The two heroes then return to their home universe and set about shepherding the rest of humanity to a knew home. Except Renark decides to stay behind and watch the universe shrink out of existence.

The second half of the novel has the human race fighting for its survival in a strange alien deathmatch known as the Blood Red Game due to the way in which the game affects those who play it. A new protagonist, Adam Roffrey, returns to the newly stabilised Shifter system in search of his wife, Mary, and along the way he also picks up two of Renark’s other companions, Paul Talfyn and Willow Kovacs, and when the four of them return to the human refugees they find themselves getting dragged into the Game along with the rest of humanity. In the end it is the combination of their mental strength and Asquiol and Mary’s connection to the multiverse that allows the human race to win out, and the race steps forward to claim its birthright.

It’s Place in the Multiverse

It’s fair to say that there are a lot of links between this early novel and Moorcock’s later works. In the original novel (and the first novella from 1962), the central character was named (Jon) Renark the Wanderer, but in 1994 Moorcock made a couple of minor revisions to the story, one of which was to change the character’s name to Renark von Bek, tying him to the von Bek family found in several other Eternal Champion story arcs. This, along with the inclusion of Mary the Maze referring to Renark by the name of Corum when she meets him confirms his place as one of the incarnations of the Eternal Champion at the very least, but what if there’s more to it than that?

During his face-to-face with the Originators, Renark is told that he has…

“…a mighty spirit that is too great for the flesh that chains it. It must be allowed to spread, to permeate the multiverse…”

This could easily be taken as confirmation of Renark’s role as an incarnation of the Eternal Champion. However, coupled with his decision to stay behind at the final contraction of the human universe, and the very specific suggestion that he needs to spread his spirit through the multiverse, it could also be argued that Renark is the ur-Champion, the source of all the other Champions throughout the multiverse. Given that the original novella of The Sundered Worlds was written and published around the same time as the original novella version of The Eternal Champion it’s certainly tempting to think there’s more to Renark’s sacrifice than just wanting to see the world end, figuratively speaking.

It’s worth noting that Renark isn’t the only incarnation of the champion in this novel. In the novel version of The Eternal Champion (1970), one of the names John Daker assigns to himself is Asquinol (later revised to Asquiol), thereby making Asquiol both companion to the champion and an incarnation of the champion at the same time. As with many of the revisions Moorcock would make to his works over the years, this adds another strand to the web of connections between the many worlds of the multiverse.

The novel’s narrative itself starts at the edge of the known galaxy, on the world of Migaa and in a city that shares the same name. It’s here that Renark joins up with his loyal companion, Asquiol of Pompeii, and a couple of other characters before heading off into the mysterious Shifter system. Coincidentally, in his 2010 Doctor Who novel, The Coming of the Terraphiles, Moorcock includes a similar world on the edge of reality, Miggea, where humanity awaits the end of the universe and competes for the fabled Arrow of Law, another of Moorcock’s recurring motifs. I’ll come back to this last detail later. In that same book, there’s also a passing mention of a certain Renark, Lord of the Rim…

Arriving in the Shifter, Renark (and later the rest of the human refuse that follows him) finds a system made up of eleven planets positioned equidistant from the twin stars at the heart of the system. Shrugging off an attack from one of those worlds, Renark and crew are guided down to the world of Entropium, where they meet with some of the seemingly apathetic locals. More importantly, this is where Renark has his encounter with Mary the Maze, and begins to grasp the enormity of the task ahead of him. It is Mary who points him in the direction of the alien Shaarn, the civilisation responsible for the Shifter’s headlong journey through the multiverse, and the Shaarn in turn guide our heroes to the world of Roth, where they meet the aforementioned Originators.

The experiences of Renark and Asquiol on Roth, and Roffrey’s later journey there in search of Mary, present the reader with an absolutely note-perfect encounter with the forces of chaos and entropy, using descriptions that are simultaneously disturbing and disorienting, and yet at the same time poetic and strangely beautiful. This ever-present sense of entropy, and the gradual but inexorable corruption of everything is a theme that Moorcock will return to over and over again throughout his works. And ever-opposing those forces of chaos will be the Eternal Champion, and the equally implacable forces of cosmic law and order.

It’s difficult to pin down where the Originators fit into this cosmology. There are moments where it feels like they are the prototypical agents of law, but there are also hints that they represent the original cosmic balance, the force that strives to maintain parity between the two sides of the conflict. That said, when their plan for humanity comes to fruition, and Asquiol leads the survivors of the exodus to their place of dominance in a new universe, there does seem to be a strong suggestion that the human race may potentially end up becoming the agents of both law and chaos in the multiverse. As Mary says to Asquiol in the Epilogue:

“We have to keep trying to cut justice from the stuff of chaos.”

Which brings us right back to that competition to win the Arrow of Law in The Coming of the Terraphiles.

Final Thoughts

I’ve read this book maybe half a dozen or so times in the past, but it’s only in this most recent reading that I’ve seen a lot of the links and themes I discuss in this article. It’s deceptively complex, and that complexity could easily be overlooked if read out of context or as a standalone novel. Are those links deliberate, or just a coincidence that I’ve latched on to in order to make this early foray into the multiverse fit into the rest of Moorcock’s works? I’d like to think at least some of it was planned for, and that even back in the early sixties when he started writing the first parts of this story, he had a sense of where he wanted these themes to go in the long term.

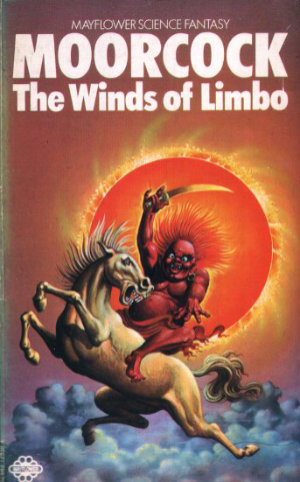

My next stop on the multiversal road will be courtesy of The Winds of Limbo, also known as The Fireclown. It’s a tale of government interference, media manipulation, false idols, and false accusations, and despite having been published almost fifty years ago may still have something to teach us about our relationship to the world around us.